Thursday, March 24, 2011

The history in medicine

No, not the history of medicine (which is fascinating, but better covered by lots smarter people than me. Sites like the National Library of Medicine serve up some nice treats in that vein, especially the images like this one.

But I am more thinking about the nature of history that is less tangible, the things that persist in our practices (of course, the practice of medicine, in my case), which are subverted into the present without shape or form, but real in that they sort of line the basic parameters of what we perceive, and more importantly, how we perceive. No, not in some conspiratorial manner, as there is no 'agent' if you will, no governing body or authority that deems it so, but more of an opaque background and lens that shapes the way we act, without a conscious presence. And yet, it is pervasive and inescapable within the current activities of medicine and medical science (and equally so in virtually any other domain, no matter the 'realness' of the observations. For an example from the more purportedly 'hard sciences,' see the nice piece by Traweek on the culture of physics, for example: Beamtimes and Lifetimes).

Dali's representation, "The persistence of memory" is about as useful an image to convey this, the way these misshapen events linger, as I have found. Plus it gets Dali into a blog.

For example, I think folks would universally recognize that Alzheimer's disease is a significant and growing challenge to the medical system, from the patients and caregivers through the whole therapeutic and health care system. But the history of Alzheimer's is fraught with indecision and difficulty, from the first 'recognition' through current research and interventions (see the Atlas, first chapter on history, but all the detail you like in a long download). The simple history is that cognitive decline was historically an expected outcome of long lives, such that the period of life after 60 (when lifespan was less than 50) was called the "senile period." It was when folks presented with 'senile' symptoms presented earlier in life that they were seen as some novel pathology (the index case was a 50 yo woman). There was some interesting debate about the cause of the disease and it is likely that many readers know that there are abnormal formations or 'plaques' that from in the brain and appear to cause the symptoms. Of course, other kinds of dementias also have these plaques (in even 'normal aging, as well in specific neurological disorders, such as Pick's disease). But we can leave the details and think about the simple history of the first, or 'index' case. A woman, not old, shows up in the office and has lots of trouble with memory, personality changes and activities of daily life. The 'naming' of the disorder takes some years, and that naming identifies a set of gross symptoms, a collection now called a disease, Alzheimer's.

Fast forward. With advanced brain imaging techniques, functional MRIs, PET scans and others, the actual activity and state of the brain can be observed and used to make this kind of diagnosis. Of course, this means that some folks who might not have had Alzheimer's based on clinical presentation do meet the criteria for the disease and folks who look like they must have Alzheimer's do not meet the diagnostic criteria.

Now identified, the hunt for treatment (and of course, the "Cure") is engaged enthusiastically. Current R & D spending for treatment is approaching $1 Billion (costs of care, for contrast, are estimated to be around $168 Billion dollars). The focus of that research is my interest here, and the place where the persistence of memory both lurks and drives activity.

The vast majority of that expenditure, both public and private, is aimed at developing drug interventions that mitigate some of the cellular processes that are seen in the disease and its progression, from inhibiting plaque development to improving glucose utilization in the brain. But the disease was not recognized because of tangles in the brain, impaired glucose metabolism or increased baseline inflammation. Alzheimer's was a disease of behavior, not biochemistry (mostly because we did not have access to things like "biochemistry" when most clinical diseases were 'recognized.'). The legacy of the 'clinical' entity haunts the research practices today, where the focus on treatment is always viewed through the notion that the basic biology must have some direct connection to the clinical entity. So, like all the 'research' programs that were born out of the recognition of clinical diseases, the biochemical correlates are always somehow related to the clinical manifestations in some causal, meaning linear, way.

The analogy is that by looking at the weather today (the current end stage outcome of all weather up to this point), we can find some 'knowledge' of the weather a week ago, or a month ago (biochemical activity). But that is what we are assume, and then invert that, to work from our assumptions in the biochemistry to the disease.

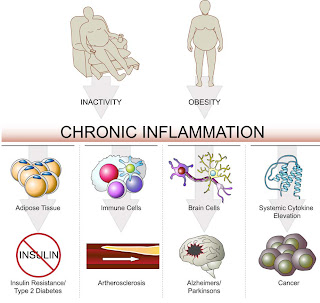

This commitment to maintaining a connection between the end-stage clinical outcomes and basic biological processes comes at a great cost. The clinical entities become constituencies, competing for limited resources. It isn't about understanding the commonalities in chronic disease and addressing those, so the benefits of that therapy accrue to any of the end-stages. The researcher in Alzheimer's and cancer, in kidney disease and in lupus are engaged in similar and even parallel research, as the basic processes in biology are similar across the body. But rather than jointly strive to understand and address a basic issue, like low-level, persistent inflammation, or errant protein folding that is common to may diseases, the historical context of the 'clinical' disease restricts and balkanizes understanding. Of course, from an industry and funder perspective, this is a good thing, called 'focus.' No one seems to mind that the object of that focus is a mirage.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment