In an earlier post, I described the importance of circadian rhythm in organizing basic physiological processes. The significance of this (and shorter and longer period rhythms) rhythm is usually inversely proportional to its discussion, especially in medicine. But occasionally there is a 'flyer,' some paper that just shoots of of the rough and lands on the map.

"Shift Work in Nurses: Contribution of Phenotypes and Genotypes to Adaptation"

Interesting in that it points out a number of the obvious issues with changing patterns of shift work, but also correlations with particular genetic features, which is pretty novel. Good read, just for all the background about the health risks with shift work.

And for a bit more entertainment, a very nice piece by one of the deans of chronobiology (no, I did not just make that up!), commenting on sleep and the training of residents., here.

The utility of this kind of training reduced the residents to such sleep deprivation that patients simply become obstacles to sleep. Easy to grind the empathy out of people. Not too sure what to expect with the new training laws. Maybe I'll find a younger doctor and see.

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

Friday, April 8, 2011

Lobbyist for the Dead

Medicine, if anything, is a daunting practice. And the US version is particularly burdensome, as the myth of heroic medicine is reiterated everywhere and by virtually everyone. A local radio station (otherwise best know for repulsive talk and hiring ex-politicians after they make parole (really)) is running a 'fundraiser' for the local children's hospital.

Medicine, if anything, is a daunting practice. And the US version is particularly burdensome, as the myth of heroic medicine is reiterated everywhere and by virtually everyone. A local radio station (otherwise best know for repulsive talk and hiring ex-politicians after they make parole (really)) is running a 'fundraiser' for the local children's hospital. They are running promotional stories from parents with gut wrenching tales of sick children saved by the hospital staff and endearing tales of how individuals at the hospital, from surgeons to clerks, nurses to administrators, provided for their every need. Of course the heroic stories are inspiring and wonderful for the folks involved and engender a belief that the clinical teams that can perform these heroics are due our gratitude and support.

Great stories, but really not informative for consumers, as the best of medicine are the events that are way outside of the norm. The way it always works is that half the folks get above average care and half the folks get below average care. No way around that. The challenge for most folks, hoe do you tell the difference?

One of the ways is to look at the number of medical errors that are reported. That reporting, however is not just shoddy, it is contrary to a culture of medicine that excels at generating heroic stories (one reason I cannot watch lots of evening TV is that I cannot suspend my disbelief long enough to entertain doctors or lawyers as heroes). In a landmark review, the Institute of Medicine generated this report on medical error in the US. It was, of course, attacked by institutional and academic medicine, suggesting that about 350 people a day are killed (yup, killed) by medical treatment (no, and they were not going to die anyway) and many more injured. Later estimates, based on better data from Australia and New Zealand suggested that a comparable rate of error for the US would be 2.5X greater. The 'cure' for this rampant, hidden disease that was likely killing over 500 patients a day and injuring many more was, get this, to be honest about mistakes! I know, I know, crazy talk. But that was the idea and the model was what is done in the airline industry, where reporting mistakes is not met with punitive reactions nor lawsuits. That method allows the airline industry and regulators to cooperate on understanding potential system-level drivers of error, as well as individual events. The goal was to reduce the level or error 50% in 5 years. As lots of the errors hinged on simple mistakes aggregated at the same time and the same place, just working on the minor mistakes would reduce the catastrophic mistakes (this is a function of non-linearities in iterative systems and conforms to a power law. More later). For lots of conflicting and hidden reasons, this never got (nor gets) done. But some diligent folks keep at it, at least telling the story. A recent article in Health Affairs (unfortunately, not about hospital-based TV shows) that really looked at individual patients found that medical error rates are astronomically higher than folks recognized. So even the estimates in that issue of HA dedicated to quality, are likely to underestimate the problem by 90%. Updating their figures, medical errors cost the medical system about $170 Billion annually and "social costs" are in the trillions. Yikes!

One of the ways is to look at the number of medical errors that are reported. That reporting, however is not just shoddy, it is contrary to a culture of medicine that excels at generating heroic stories (one reason I cannot watch lots of evening TV is that I cannot suspend my disbelief long enough to entertain doctors or lawyers as heroes). In a landmark review, the Institute of Medicine generated this report on medical error in the US. It was, of course, attacked by institutional and academic medicine, suggesting that about 350 people a day are killed (yup, killed) by medical treatment (no, and they were not going to die anyway) and many more injured. Later estimates, based on better data from Australia and New Zealand suggested that a comparable rate of error for the US would be 2.5X greater. The 'cure' for this rampant, hidden disease that was likely killing over 500 patients a day and injuring many more was, get this, to be honest about mistakes! I know, I know, crazy talk. But that was the idea and the model was what is done in the airline industry, where reporting mistakes is not met with punitive reactions nor lawsuits. That method allows the airline industry and regulators to cooperate on understanding potential system-level drivers of error, as well as individual events. The goal was to reduce the level or error 50% in 5 years. As lots of the errors hinged on simple mistakes aggregated at the same time and the same place, just working on the minor mistakes would reduce the catastrophic mistakes (this is a function of non-linearities in iterative systems and conforms to a power law. More later). For lots of conflicting and hidden reasons, this never got (nor gets) done. But some diligent folks keep at it, at least telling the story. A recent article in Health Affairs (unfortunately, not about hospital-based TV shows) that really looked at individual patients found that medical error rates are astronomically higher than folks recognized. So even the estimates in that issue of HA dedicated to quality, are likely to underestimate the problem by 90%. Updating their figures, medical errors cost the medical system about $170 Billion annually and "social costs" are in the trillions. Yikes! |

| Children's Cemetery, Colma, IT (S. Lenz) |

But why is this news? Remember that heroic culture of medicine? The very language used tells us how to understand the problem. When young cancer patients at the local children's hospital is treated and the disease does not respond to the therapy, they are said to have 'failed chemotherapy.' In a place where failure is not a option, those who fail are all sent to the same place, where their own tales of heroism lie dormant, slowly forgotten. And the tales of perpetual heroics continue to resound, from the media, from our friends and families, from our own medical caregivers. Just seems to me that the dead need a better lobby. Then maybe we'd figure out how to keep our medical system from killing so many of us.

Thursday, April 7, 2011

Lies, Damn lies, Medical reporting....

As I was innocently driving down the FL Turnpike, for the Cleveland Clinic (restarting a cardiovascular clinical trial), I was assaulted by a story on NPR about how a progesterone gel was used to reduce premature births in women 'diagnosed' with a 'short cervix.' First, I think some of the girls on my basketball team should be diagnosed with 'short stature' and maybe we can get some kind of intervention. The conversion of physical characteristics into pathology is, itself, a pathology. But that isn't the part that got me.

In the course of the report, they stated that women with short cervix had rates of premature delivery of up to 50% and those that used the progesterone gel had a 45% reduction in premature births. Sounds great. So the story goes on to 'highlight' one woman who entered the trial and was in the group that had the active cream and delivered a full-term baby. The quote from NPR was the therapy 'worked.' Huh? How would they know she wasn't going to go to full-term without the drug? Huh? Science reporting is the only thing lazier than science itself. I mean, NPR? What are they trying to prove, that they are just as bad as commercial outfits?

Well, I had to look at the real numbers, to see what the likelihood of pre-term delivery in the study was and it was 23% of 229 women (in the control arm), meaning around 52 births. Also means the majority of women with the diagnosis of 'short cervix' don't have premature babies. And in the treatment arm (same number of women, I think), about 32 women have pre-term deliveries, despite the drug. So that means the drug 'prevented' about 20 pre-term births out of 229 total births. I mean not bad, but hardly earth shattering, especially for the horribly misleading commentary about the woman who they followed.

Good news for the pharmaceutical company is that soon all the women in the US with 'short cervix' will get this drug, even though the vast majority will not benefit and there will still be lots of pre-term births. Oh, and we will all pay the millions necessary to implement the therapy. But that's the way we apparently like it.

In the course of the report, they stated that women with short cervix had rates of premature delivery of up to 50% and those that used the progesterone gel had a 45% reduction in premature births. Sounds great. So the story goes on to 'highlight' one woman who entered the trial and was in the group that had the active cream and delivered a full-term baby. The quote from NPR was the therapy 'worked.' Huh? How would they know she wasn't going to go to full-term without the drug? Huh? Science reporting is the only thing lazier than science itself. I mean, NPR? What are they trying to prove, that they are just as bad as commercial outfits?

Well, I had to look at the real numbers, to see what the likelihood of pre-term delivery in the study was and it was 23% of 229 women (in the control arm), meaning around 52 births. Also means the majority of women with the diagnosis of 'short cervix' don't have premature babies. And in the treatment arm (same number of women, I think), about 32 women have pre-term deliveries, despite the drug. So that means the drug 'prevented' about 20 pre-term births out of 229 total births. I mean not bad, but hardly earth shattering, especially for the horribly misleading commentary about the woman who they followed.

Good news for the pharmaceutical company is that soon all the women in the US with 'short cervix' will get this drug, even though the vast majority will not benefit and there will still be lots of pre-term births. Oh, and we will all pay the millions necessary to implement the therapy. But that's the way we apparently like it.

Thursday, March 31, 2011

Prostate profits

A recent decision by Medicare to cover a new vaccine by Dendreon (Provenge) for advanced prostate cancer (development story here) was anticipated by lots of speculation on the reimbursement price. I wanted to reflect on this as kind of a general case in medical 'science.'

Certainly, advanced prostate cancer is no picnic. But it is likely vastly over-treated, especially in older (> 70 yo) men. Nevertheless, goals to extend life through more treatment continue to drive research and folks, like Dendreon, occasionally can persevere and bring new technologies to market that demonstrate some advantages. In the case of Dendreon, the advantages are an extended mean life expectancy for roughly 21 months to 25 months. Four months. Two notions I'd like to ponder here. The first is simple, just about the mean or average, where it is just that, an average and some folks in both groups had higher and lower life expectancies. One quirk of these kinds of statistics is that the 'average' cannot be applied to individual cases. Huh? A clinician could recommend this vaccine to patients saying something like, "In a published study, folks in the group taking the active drug survived, on average, 4 months longer than those who did not." If the patient hears, "If I take this drug, I will survive an extra four months," they are wrong. Some of the patients taking the drug may have survived 4 months longer, maybe not. Certainly, some patients survived more that an extra four months, maybe a lot more. And then some died before they reached four months. Oh, and some died, even though they were taking the drug, sooner than the average person NOT taking the drug. So any individual patient could have any of these individual outcomes. That is now a bitch to figure out. Sorry.

Okay. Gamble with the drug. Just have to have someone pay the freight. $93,000. You heard me. $93 K, for 3 treatments in a month. Of course, as a monopoly, what's a payer to do? Either deny coverage (generate outrage) or suck it up. The beauty of this example is myriad. Since Medicare only pays 80%, there is an $18,600 co-pay. Some folks might have that, or part of it, covered by supplemental insurance, but it still will be a chunk of change. Think of the bank of dunners at the call center, haranguing elderly cancer patients for the co-pay. Better yet, the mark-up that will be charged by clinicians, but embedded within the $93 K. that works because Dendreon will give discounts to big purchasers, who then can mark it back to the $93 K and pocket the difference. Of course, that would increase the likelihood of prescribing, one would think....

Okay. Gamble with the drug. Just have to have someone pay the freight. $93,000. You heard me. $93 K, for 3 treatments in a month. Of course, as a monopoly, what's a payer to do? Either deny coverage (generate outrage) or suck it up. The beauty of this example is myriad. Since Medicare only pays 80%, there is an $18,600 co-pay. Some folks might have that, or part of it, covered by supplemental insurance, but it still will be a chunk of change. Think of the bank of dunners at the call center, haranguing elderly cancer patients for the co-pay. Better yet, the mark-up that will be charged by clinicians, but embedded within the $93 K. that works because Dendreon will give discounts to big purchasers, who then can mark it back to the $93 K and pocket the difference. Of course, that would increase the likelihood of prescribing, one would think....

Lastly, this fits into the idea of a 'prefect' medical advance. The therapy isn't curative, so the patient stays in the pool of revenue generating cases and the therapy does not require a reduction in any other intervention. The cost simply gets added to all the existing costs. And if the average patient does get the 4 months, that is 4 more months of production, in terms of opportunities to render care. Every one wins. Except for the payers. Oh, and the poor slob who would have survived much longer if no one would have diagnosed him with prostate cancer in the first place.

Certainly, advanced prostate cancer is no picnic. But it is likely vastly over-treated, especially in older (> 70 yo) men. Nevertheless, goals to extend life through more treatment continue to drive research and folks, like Dendreon, occasionally can persevere and bring new technologies to market that demonstrate some advantages. In the case of Dendreon, the advantages are an extended mean life expectancy for roughly 21 months to 25 months. Four months. Two notions I'd like to ponder here. The first is simple, just about the mean or average, where it is just that, an average and some folks in both groups had higher and lower life expectancies. One quirk of these kinds of statistics is that the 'average' cannot be applied to individual cases. Huh? A clinician could recommend this vaccine to patients saying something like, "In a published study, folks in the group taking the active drug survived, on average, 4 months longer than those who did not." If the patient hears, "If I take this drug, I will survive an extra four months," they are wrong. Some of the patients taking the drug may have survived 4 months longer, maybe not. Certainly, some patients survived more that an extra four months, maybe a lot more. And then some died before they reached four months. Oh, and some died, even though they were taking the drug, sooner than the average person NOT taking the drug. So any individual patient could have any of these individual outcomes. That is now a bitch to figure out. Sorry.

Okay. Gamble with the drug. Just have to have someone pay the freight. $93,000. You heard me. $93 K, for 3 treatments in a month. Of course, as a monopoly, what's a payer to do? Either deny coverage (generate outrage) or suck it up. The beauty of this example is myriad. Since Medicare only pays 80%, there is an $18,600 co-pay. Some folks might have that, or part of it, covered by supplemental insurance, but it still will be a chunk of change. Think of the bank of dunners at the call center, haranguing elderly cancer patients for the co-pay. Better yet, the mark-up that will be charged by clinicians, but embedded within the $93 K. that works because Dendreon will give discounts to big purchasers, who then can mark it back to the $93 K and pocket the difference. Of course, that would increase the likelihood of prescribing, one would think....

Okay. Gamble with the drug. Just have to have someone pay the freight. $93,000. You heard me. $93 K, for 3 treatments in a month. Of course, as a monopoly, what's a payer to do? Either deny coverage (generate outrage) or suck it up. The beauty of this example is myriad. Since Medicare only pays 80%, there is an $18,600 co-pay. Some folks might have that, or part of it, covered by supplemental insurance, but it still will be a chunk of change. Think of the bank of dunners at the call center, haranguing elderly cancer patients for the co-pay. Better yet, the mark-up that will be charged by clinicians, but embedded within the $93 K. that works because Dendreon will give discounts to big purchasers, who then can mark it back to the $93 K and pocket the difference. Of course, that would increase the likelihood of prescribing, one would think....Lastly, this fits into the idea of a 'prefect' medical advance. The therapy isn't curative, so the patient stays in the pool of revenue generating cases and the therapy does not require a reduction in any other intervention. The cost simply gets added to all the existing costs. And if the average patient does get the 4 months, that is 4 more months of production, in terms of opportunities to render care. Every one wins. Except for the payers. Oh, and the poor slob who would have survived much longer if no one would have diagnosed him with prostate cancer in the first place.

Thursday, March 24, 2011

The history in medicine

No, not the history of medicine (which is fascinating, but better covered by lots smarter people than me. Sites like the National Library of Medicine serve up some nice treats in that vein, especially the images like this one.

But I am more thinking about the nature of history that is less tangible, the things that persist in our practices (of course, the practice of medicine, in my case), which are subverted into the present without shape or form, but real in that they sort of line the basic parameters of what we perceive, and more importantly, how we perceive. No, not in some conspiratorial manner, as there is no 'agent' if you will, no governing body or authority that deems it so, but more of an opaque background and lens that shapes the way we act, without a conscious presence. And yet, it is pervasive and inescapable within the current activities of medicine and medical science (and equally so in virtually any other domain, no matter the 'realness' of the observations. For an example from the more purportedly 'hard sciences,' see the nice piece by Traweek on the culture of physics, for example: Beamtimes and Lifetimes).

Dali's representation, "The persistence of memory" is about as useful an image to convey this, the way these misshapen events linger, as I have found. Plus it gets Dali into a blog.

For example, I think folks would universally recognize that Alzheimer's disease is a significant and growing challenge to the medical system, from the patients and caregivers through the whole therapeutic and health care system. But the history of Alzheimer's is fraught with indecision and difficulty, from the first 'recognition' through current research and interventions (see the Atlas, first chapter on history, but all the detail you like in a long download). The simple history is that cognitive decline was historically an expected outcome of long lives, such that the period of life after 60 (when lifespan was less than 50) was called the "senile period." It was when folks presented with 'senile' symptoms presented earlier in life that they were seen as some novel pathology (the index case was a 50 yo woman). There was some interesting debate about the cause of the disease and it is likely that many readers know that there are abnormal formations or 'plaques' that from in the brain and appear to cause the symptoms. Of course, other kinds of dementias also have these plaques (in even 'normal aging, as well in specific neurological disorders, such as Pick's disease). But we can leave the details and think about the simple history of the first, or 'index' case. A woman, not old, shows up in the office and has lots of trouble with memory, personality changes and activities of daily life. The 'naming' of the disorder takes some years, and that naming identifies a set of gross symptoms, a collection now called a disease, Alzheimer's.

Fast forward. With advanced brain imaging techniques, functional MRIs, PET scans and others, the actual activity and state of the brain can be observed and used to make this kind of diagnosis. Of course, this means that some folks who might not have had Alzheimer's based on clinical presentation do meet the criteria for the disease and folks who look like they must have Alzheimer's do not meet the diagnostic criteria.

Now identified, the hunt for treatment (and of course, the "Cure") is engaged enthusiastically. Current R & D spending for treatment is approaching $1 Billion (costs of care, for contrast, are estimated to be around $168 Billion dollars). The focus of that research is my interest here, and the place where the persistence of memory both lurks and drives activity.

The vast majority of that expenditure, both public and private, is aimed at developing drug interventions that mitigate some of the cellular processes that are seen in the disease and its progression, from inhibiting plaque development to improving glucose utilization in the brain. But the disease was not recognized because of tangles in the brain, impaired glucose metabolism or increased baseline inflammation. Alzheimer's was a disease of behavior, not biochemistry (mostly because we did not have access to things like "biochemistry" when most clinical diseases were 'recognized.'). The legacy of the 'clinical' entity haunts the research practices today, where the focus on treatment is always viewed through the notion that the basic biology must have some direct connection to the clinical entity. So, like all the 'research' programs that were born out of the recognition of clinical diseases, the biochemical correlates are always somehow related to the clinical manifestations in some causal, meaning linear, way.

The analogy is that by looking at the weather today (the current end stage outcome of all weather up to this point), we can find some 'knowledge' of the weather a week ago, or a month ago (biochemical activity). But that is what we are assume, and then invert that, to work from our assumptions in the biochemistry to the disease.

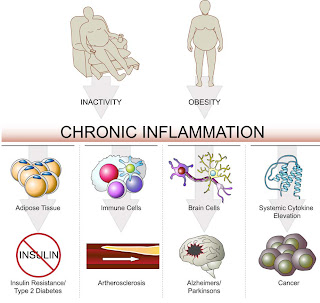

This commitment to maintaining a connection between the end-stage clinical outcomes and basic biological processes comes at a great cost. The clinical entities become constituencies, competing for limited resources. It isn't about understanding the commonalities in chronic disease and addressing those, so the benefits of that therapy accrue to any of the end-stages. The researcher in Alzheimer's and cancer, in kidney disease and in lupus are engaged in similar and even parallel research, as the basic processes in biology are similar across the body. But rather than jointly strive to understand and address a basic issue, like low-level, persistent inflammation, or errant protein folding that is common to may diseases, the historical context of the 'clinical' disease restricts and balkanizes understanding. Of course, from an industry and funder perspective, this is a good thing, called 'focus.' No one seems to mind that the object of that focus is a mirage.

Thursday, March 10, 2011

Remystifying data

I know, oxymoron. The esoteric and mysterious is preferable to the mundane for aesthetic reasons, but, for practical action, the mundane in the domain.

I wanted to revisit the placebo, as some folks commented on it and there is more useful

information than that critique (if that was at all useful). In the clinical trial, we look at outcomes from the treatment (or active) group and the sham (placebo) group. It is pretty common, especially when looking at things like pain, that the placebo group has positive result (which I already described). If the active group has a positive result that enough better than the placebo group, then one can say the results are ‘significantly better.’ Significance is a technical term here, commonly meaning that the number of times we find these results by chance are less that 5 time in 100 similar studies. Significance is a tricky notion, in that the amount of difference needed for something to be significant depends, in part, on how effective the treatment is and how many people are in the study. Really effective treatments need less people. Less effective treatments need more. So saying that there is a ‘statistically significant’ difference in a treatment over a placebo doesn’t give you lots of information. A better way to think about it is to see how many patients have to be treated before the effect of the treatment is seen in one patient. This is called ‘numbers needed to treat’ or NNT.

information than that critique (if that was at all useful). In the clinical trial, we look at outcomes from the treatment (or active) group and the sham (placebo) group. It is pretty common, especially when looking at things like pain, that the placebo group has positive result (which I already described). If the active group has a positive result that enough better than the placebo group, then one can say the results are ‘significantly better.’ Significance is a technical term here, commonly meaning that the number of times we find these results by chance are less that 5 time in 100 similar studies. Significance is a tricky notion, in that the amount of difference needed for something to be significant depends, in part, on how effective the treatment is and how many people are in the study. Really effective treatments need less people. Less effective treatments need more. So saying that there is a ‘statistically significant’ difference in a treatment over a placebo doesn’t give you lots of information. A better way to think about it is to see how many patients have to be treated before the effect of the treatment is seen in one patient. This is called ‘numbers needed to treat’ or NNT. Here is an example: If a 40% of folks in the placebo group respond to a treatment and 50% of the active respond, then we know that 4 out of 10 responders in the active group (where 5 out of 10) are likely to be responding to the ‘placebo,’ so, after we subtract those from the active, we have 1 in 10. That means that 10 people have to be treated for 1 to show a response to the treatment. So, a treatment may be ‘significantly’ better than the placebo, but the number of patients who actually benefit may not be all that high. Here is some data on pain meds. Pretty clear that the best ones only provide the level of benefit to 2 out of 3 patients.:

Table 1: The Oxford league table of analgesic efficacy (commonly used and newer analgesic doses)

What is really interesting is when you start adding in the negative effects of treatment and then comparing the ‘benefit’ to the harm. The folks at www.thennt.com are kind enough to do that for us in some areas. May be surprising that mammograms are NOT beneficial and PSA (prostate cancer screening) does more harm than good. But that never stopped us from pursuing them. Oh, and if your really want to have some fun, next time your health care provider wants you to start a drug, ask then what the NNT is, so you can make a proper determination.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)